Tim Clarkson, Scotland’s Merlin: A Medieval Legend and Its Dark Age Origins, John Donald, 2016. Amazon US $22 PB, $8 Kindle.

Tim Clarkson’s new book, Scotland’s Merlin, was a lovely break from my usual plague reading. Merlin is one of the few Arthurian characters who can stand alone from the Arthurian corpus as the Welsh figure Myrddin. This is not totally surprising because he was constructed from several long free-standing figures of British history and legend.

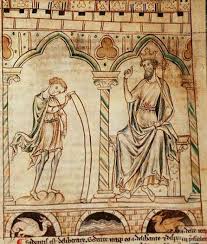

My friend Tim strongly states that Arthur’s Merlin is a figment of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s creative process (and I agree). Geoffrey drew on three legends to craft his Merlin Ambrosius (Emrys): the Dinas Emrys origin story, the Carmarthen origin story, and the prophetic wild man of the north legend. He named him well because the Merlin in Geoffrey’s History of the King of Britain is primarily a fusion of Ambrosius (Emrys) from the Historia Brittonum and a lost legend of Merlin from Carmarthen. Merlin’s interaction with Vortigern and the dragons completely comes from the Dinas Emrys story in the Historia Brittonum. The wild man Myrddin Wyllt primarily comes to the fore in Geoffrey’s last work the Vita Merlini (Life of Merlin).

Now, I suspect that the Carmarthen origin story may have been as well developed as the Dinas Emrys legend so it may have contributed a little more than Tim credits, but what that is, is complete conjecture. It must mean something though that Geoffrey is so consistent in localizing Merlin’s hereditary lands in Carmarthen/South Wales. Geoffrey’s first work, the Prophecies of Merlin, makes up a significant portion of Merlin material in this History of the Kings. We often forget that Geoffrey restricts Merlin’s role in Arthur’s life to his conception. Geoffrey claims that fans wanted more on Merlin so he produced his last work the Life of Merlin (Vita Merlini) that now begins to draw much more explicitly on the prophetic northern wild man of the woods motif. If this northern wild man, Myrddin Wyllt (the wild), is the only source of Merlin as a prophet, then he is indeed the primary source for the figure. Although Geoffrey’s Life of Merlin did not circulate nearly as much as his History, it never the less contributed to Merlin’s later development as a character, albeit without many direct textual references.

It is the northern figure, known as Myrddin Wyllt in medieval Welsh literature, that Tim traces to his origins in the Caledonian woods of southern Scotland. The name Myrddin comes from the Old Welsh word for Carmarthen, which was caer-fyrddin, a softened form of Caer-Myrddin. The modern Carmarthen is the anglicized version of Caer-Fyrddin. Although linked to a place name that would usually support it being a person’s name, that is not true in this case. Caer-Fyrddin (Caer-Myrddin) is more likely derived from the Roman Moridunum, possibly meaning sea fortress, itself derived from the pre-Roman Brittonic name. Type Caerfyrddin into google translate and listen to its pronunciation. Looking at the map here we can see that Carmarthen is placed on a river leading to a wide three-pronged fork (trident?) shaped estuary. Although not on the coast today, it is possible that it was located at the safest area in an estuary wetland. It has been the capital of the pre-Roman Demetae tribe, so indeed before the Roman period it is likely that a prince or ruler was seated at Mordunum or ‘the Sea Fortress’. Clarkson places the origins of the name as early as Caermyrddin as early as the sixth century when the Romans had been gone long enough for new placenames and origin stories to develop. Indeed, this may be a similar date and process to the Dinas Emrys story preserved first in the Historia Brittonum.

Although linked to a place name that would usually support it being a person’s name, that is not true in this case. Caer-Fyrddin (Caer-Myrddin) is more likely derived from the Roman Moridunum, possibly meaning sea fortress, itself derived from the pre-Roman Brittonic name. Type Caerfyrddin into google translate and listen to its pronunciation. Looking at the map here we can see that Carmarthen is placed on a river leading to a wide three-pronged fork (trident?) shaped estuary. Although not on the coast today, it is possible that it was located at the safest area in an estuary wetland. It has been the capital of the pre-Roman Demetae tribe, so indeed before the Roman period it is likely that a prince or ruler was seated at Mordunum or ‘the Sea Fortress’. Clarkson places the origins of the name as early as Caermyrddin as early as the sixth century when the Romans had been gone long enough for new placenames and origin stories to develop. Indeed, this may be a similar date and process to the Dinas Emrys story preserved first in the Historia Brittonum.

[On a side note, Merlin’s association with a ‘sea fortress’ may be the source of tales that Merlin has a glass house or glass isle (perhaps invisible house/fortress). Coupled with Mryddin Wyllt’s apple tree, it’s not a great fictional leap to associate Merlin with Avalon, the isle of apples.]

At some point before the ninth century the name Myrddin was transferred, or rather replaced, the name of a northern British mad prophet named Lailoken in tales told in Wales. Some of the texts of Lailoken’s northern exploits even mention that he is known to some as Myrddin. However, his name has mutated through storytelling there is a good reason to believe that a real man, Lailoken, is the historical nugget at the core of Myrddin Wyllt. Lailoken is the focus of the rest of Clarkson’s book.

The battle of Arfderydd, dated to 573 in the Annales Cambriae (AC), was one of the favorite topics of early Welsh bards. It has left its mark in the ninth century (?) Myrddin poetry, the Welsh triads (bardic memetic devices), Rhydderch Hael lore and St Kentigern legends. It was mentioned in the oldest ninth century version of the Annals Cambriae listing the British leaders on both sides. A much later recension adds that “Myrddin went mad” to the entry. All sources claim that it was an especially ferocious battle even by Dark Age standards; no quarter was given, nor apparently expected. Lailoken/Myrddin is reputed to have been a sole survivor of the losing side who goes mad from the horror of battle becoming a recluse in the Caledonian woods. He is essentially suffering from post traumatic stress syndrome or shell shock. He retreats to the woods living with a pet pig and uttering prophecies or omens from the branches of an apple tree. One of the oldest sources for Lailoken (in his own name) is in his interactions with St Kentigern in hagiography.

Perhaps the most important contribution this book makes to early British history, beyond the evolution of Merlin, is Clarkson’s analysis of the sources for the battle of Arfderydd. I agree with him that there is enough to believe that the battle took place and probably it’s location, but practically nothing else is historically credible. It became a magnet to collect the heroes of the North, generally on the winning side (of course). There is nothing that we can draw about who was actually involved, beyond the brothers Peredur and Gwrgi who defeated Gwenddolau (listed in the AC). All of the other figures were drawn to the lore of this battle like moths to a flame. Geoffrey’s Vita Merlini even has Lailoken/ Myrddin/ Merlin change sides in the battle so he can side with the winners! (contra to all other sources)

Early Modern Antiquarians attempts to reconstruct the battle from clues primarily in the Welsh triads and Myrddin poetry jumped to the conclusion that it was a battle between pagans and Christians (for no reason whatsoever). Primarily based on this assumption, Merlin was rebranded a druid. Clarkson has a whole chapter on this that should be read by anyone who wants to claim that he was a druid! “Merlin’s underpants!” — Merlin’s reputed role as a druid or magician is based on a desire by fans of Celtic mythology and those who want to ‘enhance’ or reputedly make Arthurian lore more realistic. There is no medieval basis for any of this. Both Lailoken/Myrddin and Arthur are nothing but Christian in the medieval material.

From here Clarkson takes on a variety of topics related to the evolution of Merlin and Arthuriana particularly in northern Britain. It was all very interesting and is good material for novelists who want to use medieval lore. I really enjoyed the book and I think anyone who likes Merlin, Arthuriana, Geoffrey of Monmouth’s process, or medieval lore will enjoy it, so I heartily recommend it.

Merlin and the details of the battle of Arfderydd are now firmly in the realm of literature. As fiction, authors are free to embellish and borrow from wherever they want. I suspect that any real Dark Age figures behind these figures would be just fine with becoming mythic heroes. They knew well that this was their best bet at gaining lasting fame and the details no longer mattered in the realpolitik of their land within just a few generations after their time. Our instance to know ‘what really happened’ would have been largely lost on them. They well understood Achilles’ choice to opt for fame over being grounded in the real world with a long mortal life but soon forgotten.

As always, loving your work! Would be interested to hear where you think Camlan is. I’m trying to trace the site of King Arthur’s last battle and could do with some pointers. Thanks!

I haven’t thought about Arthuriana enough lately to really speculate. Tim does have a chapter on Arthuriana including the battles located in Scotland. He has a couple suggestions for northern locations of Camlan.

There is a Sweeney/Suibne version of the Lailoken tale (12th century?) that has long perplexed me. Does Tim mention this?

He does discuss Suibne to some extent. If you are interested in the Sweeney tale, this book would probably be of interest no matter how much he writes about Sweeney.

Haven’t read this new book but from what’s been written above, reminds me of The Quest for Merlin written by Nikolai Tolstoy published in 1985.

It was of interest to me because of the names: Merlin’s real name being Myrddin anglicised as Murdin then Merlin. Rhydderch – Roderick (my first name); my wife’s name is Merline, and one of the first places my surname occurs in the historical records is Drumelzear in the Scottish Borders identified as the place where Merlin suffered the threefold death in the river Tweed. I fancifully imagined we were all the descendants of Merlin, or, Murdin’sons 😀

Rod Murdison