As part of my research on the ‘Prayer Book of Æthelwald’ in the Book of Cerne, I found this recent article by Michelle Brown:

Michelle P Brown. (2007) “The Lichfield Angel and the Manuscript Context: Lichfield as a Centre of Insular Art” Journal of the British Archaeological Association. 160(1): 8-19.

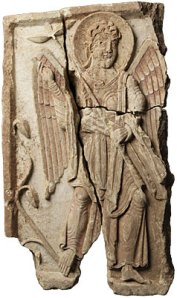

I thought that I would share some of this since I imagine many people are as eager to hear more about the Lichfield Angel as I am. Here is a picture of it from the Lichfield Cathedral website. Here is a link to the Angel Project Site with all kinds of info on its conservation etc. including a reconstruction of its paint.

The angel is on a limestone slab that was the corner of a structure, probably a house shrine similar to the St Andrew’s shrine in Pictland. It is 2.5 ft high and has traces of pigment left. The Litchfield Cathedral refers to a palate of white, red and black outlines, but Michelle Brown asserts that the colors are white, purple, and black outlines. The reconstruction shows that the angels clothing and the outline of the nimbus were gold leaf. I strongly recommend the reconstruction link above (which looks rather red to me, though red and purple can be a fine distinction). Its quite handsome when the reconstruction is complete. Michelle Brown suggests that the drilled eyes once held glass inserts. It is believed that the angel is one half of an Annunciation scene on the shrine of St. Chad. The Lichfield Cathedral has been devoted to St. Mary since the time of Bede. The Lichfield Angel has been dated to c. 800 (775-825), around the time that Lichfield Cathedral was the seat of a third Archbishop for England. The cathedral was heavily patronized by Offa of Merica (787-802), who created his own archbishop, and by his successor Coenwulf. In Coenwulf’s time, Lichfield was demoted to the status of a regular bishop to please the pope who wanted Canterbury to retain its historic domain, but he offset this demotion with further patronage.

What she is basically arguing is that the styles of the Lichfield Gospel, the Lichfield Angel and the Book of Cerne (Prayer Book of Aethelwald) all belong to the same cultural context. She is basing a lot of this on the color and design of the angels wings.

“The closest parallel to the articulation and colouring of the Lichfield angel is the eagle symbol of St John in the Book of Cerne…The subtle shades of purples and white, with black definition, are similarly handled in both works, as is the treatment of the plumage. The Lichfield angel’s Hellenistic face and hair are also echoed in the busts of the evangelists that accompany their symbols in the Book of Cerne, whilst in the latter symbol of St. Matthew, the Man, is depicted as an angel with similar if debased and simplified treatment of its wings and clinging drapery.” (p. 16)

Well, I just happened to check out Michelle Brown’s book on the Book of Cerne (1996) from the library yesterday and it has full color plates of the four evangelists. From the photos the palate looks like reddish-brown, blue, gold and white. The first thing that struck me about the miniatures in the Book of Cerne is the red-white-blue palate and the eagle has an ‘early Amercian’ style (that I remember from my parents 1960s decor). Stick a couple arrows and olive branches in its talons instead of a book, and it would look like the eagle seal. Quite a patriotic looking bird with its red and white striped wings, but I diverge from medieval programming. So anyway, these wings don’t remind me that much of the Lichfield Angel… for one thing the wings in the book of Cerne have a scalloped upper edge and again the lower part of the wings are stripped in alternating red/purple and white. The tops of the wings that are most like the Lichfield Angel also match the plumage on the body of the eagle. The most striking aspect of the evangelist miniatures is that they are beardless, but they don’t have the massive firm jaw of the angel. One of the more remarkable things about the Lichfield Angel above is the anatomic definition with gold clothing that almost looks more like armor. Brown suggests (p. 15) that the Lichfield Angel is “of the highest order”, perhaps Michael but the paradise plant and intimate gestures are more common in Annunciation scenes.

Like the evangelist symbols from the Book of Kells (shown in plates of her 1996  book), all of the symbols in Cerne are winged (Mark to the left). So I think this makes comparison of the winged man symbol for Matthew important. Here there seems to me to be a very different more fluid style. The wings have the small feathers at the top, as the Lichfield Angel does, but the entire wing is more fluid, less rigid. The upper margin is scalloped and the coloration is red/purple, blue,white and gold, in a rather random mixture. The body of the man/angel symbol is also more fluid and less antomical. The legs are visible lines through the clothing but crudely and the body has the hour-glass shape found in many Irish products. The wings on the lion of Mark to the left are similar to the angel sculpture with softer angles, but differ from the Matthew man/angel and the eagle wings of John in lack the scalloped upper edge. The coloration is more like the Matthew angel in its palate and randomness.

book), all of the symbols in Cerne are winged (Mark to the left). So I think this makes comparison of the winged man symbol for Matthew important. Here there seems to me to be a very different more fluid style. The wings have the small feathers at the top, as the Lichfield Angel does, but the entire wing is more fluid, less rigid. The upper margin is scalloped and the coloration is red/purple, blue,white and gold, in a rather random mixture. The body of the man/angel symbol is also more fluid and less antomical. The legs are visible lines through the clothing but crudely and the body has the hour-glass shape found in many Irish products. The wings on the lion of Mark to the left are similar to the angel sculpture with softer angles, but differ from the Matthew man/angel and the eagle wings of John in lack the scalloped upper edge. The coloration is more like the Matthew angel in its palate and randomness.

Overall, Brown is trying to create a group of texts and art produced or collected in early 9th century Mercia. So far she has three works linked primarily by their purple palate:

- Lichfield Gospels – mid 8th century, perhaps for the refurbishment of St Chad’s shrine (as the Lindisfarne Gospels were made for St Cuthbert’s shrine). This book she admits may have been commissioned by Lichfield from somewhere else, possibly Northumbria.

- “My studies have revealed that the book was decorated by an artist who is likely to have been accorded the privilege of studying the decorated incipits of the Lindisfarne Gospels…first hand. He devised his own simplified yet still graphically powerful responses to several of these pages (Col. Pls VI B-D) and is likely to have been working in the generation after the Lindisfarne Gospels were completed, c. 720, in the mid-8th century.This reliance did not extend to the text…more traditional Insular ‘mixed text’ in which Old Latin, Vulgate and local readings were conflated in the sort of text that were favored by the Columban paruchia” (p. 17)

- Lichfield Angel – c 800 during the expansion of the cathedral probably under Offa.

- Book of Cerne – early ninth century, that she believes was made for or in honor of Bishop Aethelwald of Lichfield (818-830)

I would be interested to hear what others who know more about these texts or have least least seen them in person think of her cluster.

I am reluctant to write anything which may sound to be criticism as I am a retired surgeon, not an historical researcher; but you, like many others, keep repeating that in your view, the ‘Lichfield Gospel’ was transcribed after the Lindisfarne Gospel. ALL of the paintings in the ‘Lichfield Gospel’ are primitive when compared with others, which suggests to me that these were made first and that this scribe provided the template which the other and later scribes copied and improved. The attempted connection of the pigments on the angel and those in the Gospel is foolish as at that time, the colours were limited and used by all scribes for many hundreds of years. Furthermore, I believe the Gospel was written in Wales, perhaps as early as the mid sixth century. Recent carbon 14 dating, as researched by Professor Pollard at Oxford is now so improved that, in his words, ‘it would be possible to date accurately within 50 years in the first millennium’ , any manuscript; It is a pity his expertise cannot be used to do just that. John Dowse FRCS

The angel looks less rigid than the Mercian sculptures at Bredon but is clearly an echo of the Gospel Book- consider the staff with its flowering tip, which in the Gospel Book is considered to have Coptic antecedants. So I wonder if the Angel could be as early as ca 740? I am sure Michelle Brown is right about the textual precedence. Bede has a passage, doesn’t he, about the vivid paintings at Wearmouth-Jarrow ? These too might have been an inspiration. As to giving the Gospels a ca. AD 550 date(!) and independent Welsh provenance, consider how undeveloped is the classicism of the Canterbury Gospels (arrived 597) or the primitivity of the Cathach…and you will soon appreciate that this idea can’t be right! It helps though to have seen them in the flesh, though, and that was a privilege indeed!